Stolen Energy | Hunting the strongest lines

/in Interview /by Stefan GoretzkiWhile we are waiting for the overflight permit in Bitterwasser, the opportunity arises to speak with Dr. Bernd Goretzki. Bernd is a meteorologist by profession and one of the founders of TopMeteo.

In Germany, he delights us every year with exceptional flights in the northern flatlands. He has been coming to Namibia for many years and has a treasure of meteorological experience that he shares with us. Especially for newbies, an entry point into the Namibian weather events is to be given here.

We are pleased to now offer the satellite images for southern Africa in WeGlide Live and in the analysis in cooperation with TopMeteo.

Bernd, how often have you been to Bitterwasser?

About ten times.

Was flying here different for you in the beginning?

Yes. Approaching the clouds leisurely does not work here. The strong thermals are often gone by the time you get there. Everything is very short-lived here, there are no permanent thermals. The energy is transformed faster and the cycles are shorter due to the high vertical speeds. What works well just like in Europe are the thick cumulus congestus clouds. With the small cumulus clouds, however, you often arrive too late.

In addition, there is the usual game with the sun in the north and not in the south – that is a constant topic. It doesn’t matter too much during the day because of the low latitude, but in the evening you are often a little confused. In addition, dusk comes very quickly, within half an hour it is completely dark. And the desert thermals often work until sunset.

In Namibia, we are also close to the equator ...

… exactly, due to the very low Coriolis force (which increases with increasing latitude), there are no pronounced pressure systems. They dissolve quickly because the air flows in or out of the pressure areas more directly and is not deflected parallel to the isobars. That is why there are no large pressure gradients and also no classic fronts. Because of the lack of fronts, there are generally almost no medium-level clouds.

Which pressure systems determine the weather here?

Namibia and South Africa form a large high plateau, which is strongly heated by the sun in summer, creating a thermal low. This leads to the fact that the intertropical convergence zone, which is itself a low-pressure trough line, bulges in the summer towards South Africa.

By the way, the thermal low is similar to Spain, where you have three very reliable weeks with good thermals from mid-July when the thermal low develops.

The low-pressure system above the highlands of southern Africa taps the humid (more) air from the north/northeast, which then carries a lot of energy. This air comes from Zambia, Botswana, and Angola to Namibia. In this airmass or at the border to the dry air, very nice thermals develop as the clouds that form out of the moisture have a very high cloud base and the beautiful cumulus congestus clouds increasingly suck the thermals into them. In principle, this is stolen energy, since evaporation took place elsewhere, but here it is released again in the form of condensation energy.

And this weather situation brings good flying weather for many days?

Usually, this is an oscillation. The humid air comes and goes again. This (north) east current can also last for around five days. Then the moisture moves to the Namib in the west, the whole of Namibia is then covered with showers and thunderstorms.

In Germany, we hope for cold air advection and the influence of high pressure. Does that work here too?

Here in the desert climate, the colder Atlantic air from the west is really bad. When it comes, the thermals might go up to 3500 m, which means really bad conditions. The air is very dry because it is incredibly heated up on the way from the Atlantic, from 15 ° to 35 ° Celsius. During this process, the relative humidity drops. It’s blue, there is direct sunshine in the cockpit at high temperatures for us, very exhausting. You often have that in September and October.

In what weather conditions can we expect the Atlantic air?

Usually, you have a powerful high-pressure system off the coast. This then shovels the Atlantic air into South Africa, from where it comes into Namibia. We are in such a situation right now. At high altitudes, this goes hand in hand with a lot of westerly winds. However, the cold air usually only pours in relatively shallowly, so it is not as deep as it is at home, for example. Above it is still the warmer air and thus a powerful inversion. That slows down the thermals accordingly, Namibian weather normally means 4500-5000 meter base.

In the afternoon we often notice strong westerly winds here?

The air from the west arrives almost every afternoon with the sea breeze front and is bone dry. The sea breeze reaches Bitterwassert between 6 p.m. and 9 p.m.

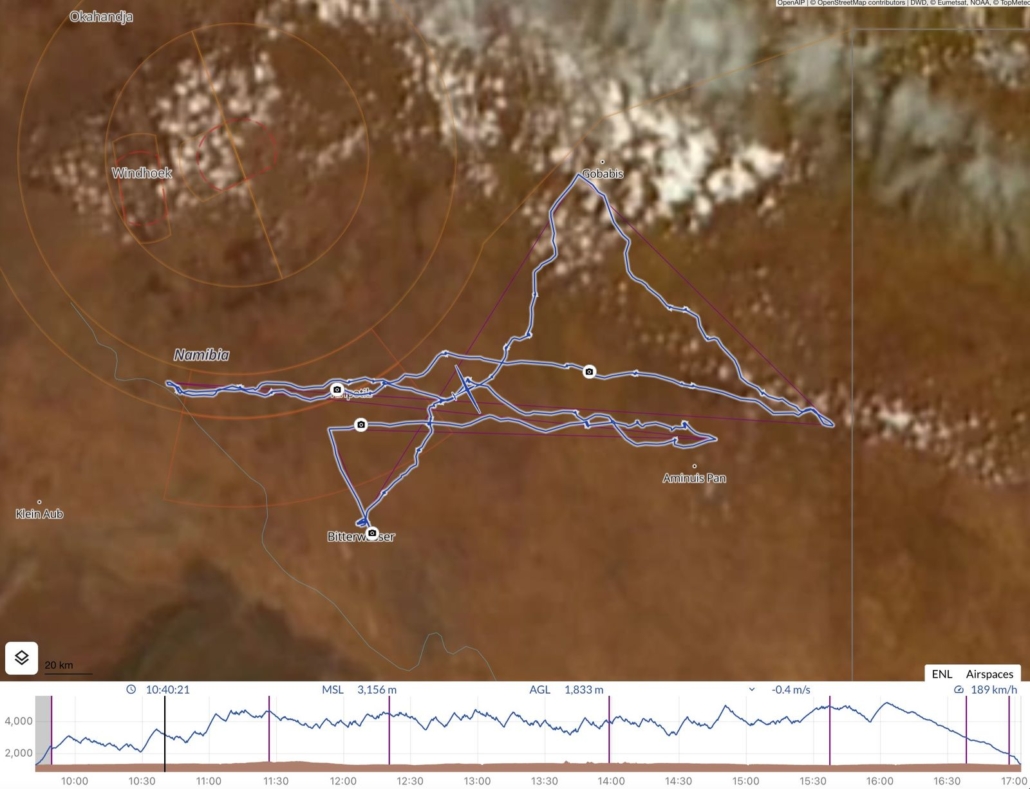

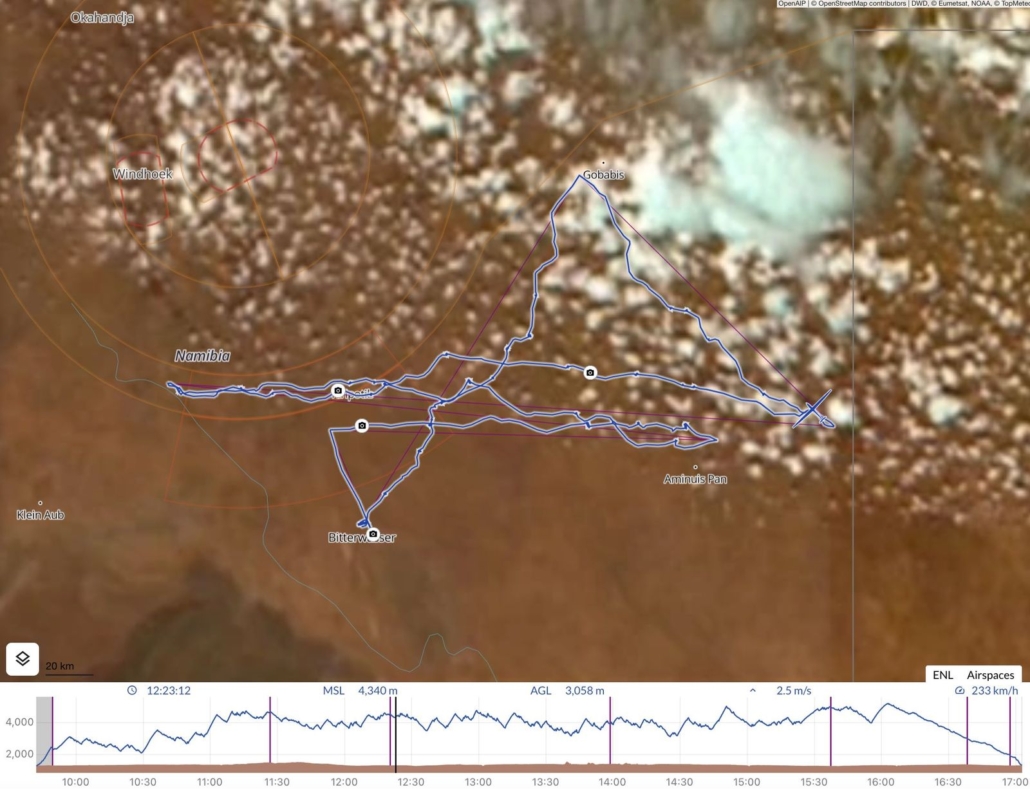

The air from last evening is mostly still over Bitterwasser in the morning. That’s why you almost always fly east in the blue in the morning – to get to the better airmass. You fly low from pan to pan and use whatever inhomogeneity there is as trigger points, i.e. pan edges, farmhouses, water points.

There is often a base jump 100 km to the east. Suddenly thermals go up to 4000 m and the first cumulants appear. The cloud base then slowly rises above Bitterwasser due to the high level of irradiation.

What happens when the two air masses meet?

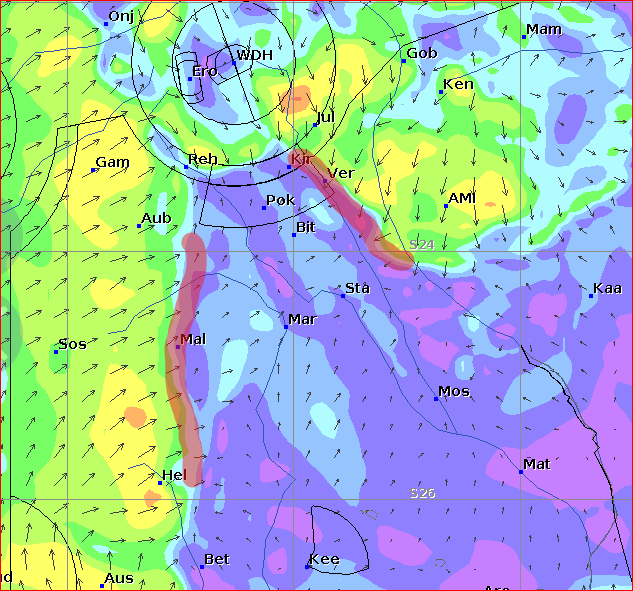

The suction effect of the more humid air mass creates really good lines at the border between the humid air in the northeast and the Namib air from the west, mostly on the border to Botswana. These lines have a northwest-southeast orientation and are actually the real convergences here.

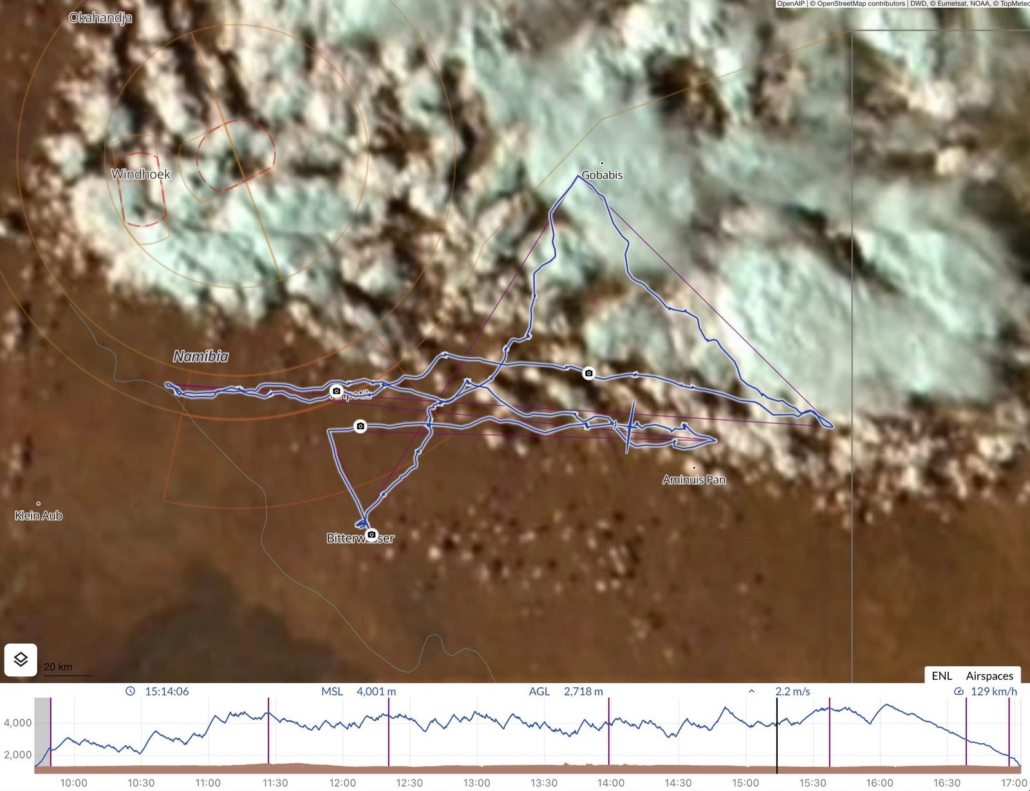

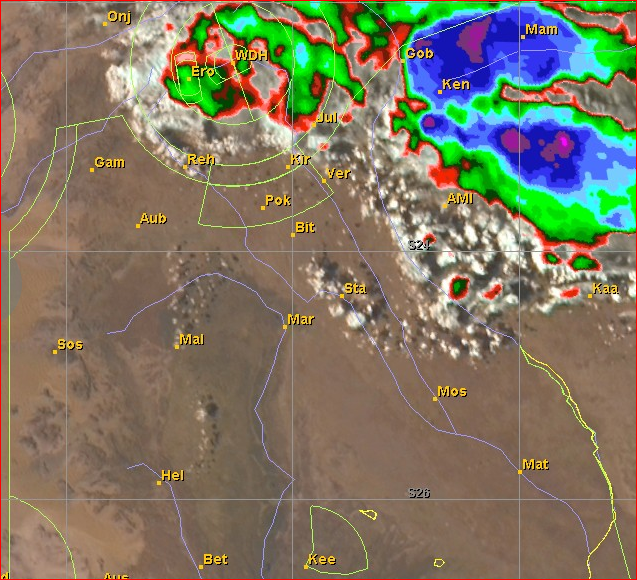

This is a wonderful transition zone in which you can often fly straight for a long time, as there is not yet enough moisture for thunderstorms or showers to develop. This zone is relatively narrow, often it is only between 50 and 80 km from too dry to too humid. The line then usually wanders in a little, sometimes it also comes in waves. The new and old lines can usually be seen nicely in the satellite image. A very good example is the flight of Reinhard Schramme and Tassilo Bode from the 12th of November.

12.11.2021: Both lines in the 10m wind field and the satellite image

The real convergence is in the west, isn't it?

That’s what people here tend to think. A lot of pilots did not have the lines in the east on their radar. The so-called convergence in the mountains in the west is not as good, it is just a transformed sea breeze front. If the east current holds against it, the sea breeze comes in a little slower and then lies over the mountains in the west for a longer period of time. Clouds then form along this line and you can then fly along quite well. But you can also be unlucky and it won’t work properly. Supported by the westerly wind, however, the line continues to the east.

The western convergence, however, is a different process than in the east. It has much less energy, the cold Atlantic air pushes itself forward and then forces the warmer air to lift. But the good line in the east and the incoming sea breeze front can also combine.

How can you spot the lines in the forecast?

I look at the 10m wind field in the forecast. The sea breeze front is becoming apparent there. The line in the east can also be seen in the wind field on the ground, there is almost no wind in the middle of it.

Is the sea breeze changed by the coastal desert?

The desert fuels the sea breeze. The Namib is a sloping plateau rising up to 900m in the east. It’s like a boiling ramp. Then there is the mountain range, which continues to heat and offers the normal thermal suction effect through its hills. However, the higher friction slows the sea breeze down a little.

Luckily, the Namib is over 80 million years old. Its age is a huge advantage, the very fine dust particles have already been carried away and there is almost no dust in the air. In combination with the extreme dryness and few clouds, this leads to very clear nights, which (hobby) astronomers are happy about.

Is that different from the Sahara?

The Sahara is much younger and often carries millions of tons of dust to Europe or even to the Amazon region. That’s the problem with flying in Morocco, you don’t have good visibility in July. In addition, there is much better radiation here without the dust in the air.

Also, the earth’s orbit around the sun is not a circle. The southern hemisphere is always a little closer to the sun in summer than the northern hemisphere in summer, which means about three percent more radiation.

Then there is the subject of thunderstorms?

When the thunderstorms come from the east, we can often fly until sunset, they rarely reach Bitterwasser. But there are situations where the moisture has already run over the entire country, up to the mountains in the west. Then the thunderstorms approach Bitterwasser from the western area in the evening after they have formed in the low mountain ranges. They basically wander with the sea breeze. It is then very difficult to avoid them, especially if they appear in lines towards the evening.

Those are days when I too prefer to land in the early afternoon. You can’t trust the forecast very much either. In such weather conditions, there is often a westerly wind at high altitudes, so that the thunderstorms or anvil clouds are blown to the east and large areas are cloud covered. All in all, thunderstorms from the west are always bad.

Thunderstorms and dust storms, as they happen here now and then, are also often related. Lots of wind, lots of gusts, no visibility. In these bad conditions, you should rather stay in the good air in front of it, wait, and not try to force a landing at home. If necessary, you can almost always go to Mariental in the South.

How does the weather change over the season?

You can have good weather here for six weeks, from early December to mid-January. That was the way people used to think. But it actually starts in November. We even know that there can be very good, but still relatively short days in October. From November to Christmas we get 35 minutes more in the evening and the sun rises earlier. That equals out to 150 km more in distance. But in principle, 1000s are possible from the end of October.

November can be very dry, as it has been this year, but the clouds will come at some point. Then there is the small rainy season at the end of November / beginning of December. That is usually a few days of rain and the pan can fill up.

And the real rainy season?

It starts in January, sometimes even right at the beginning of January. In those years, there are very few flight options from New Year’s Eve on. January basically is the most variable month, there are also incredibly good Januarys. The weather is either really good or it is interspersed with thunderstorms. It is often optically beautiful. Due to the moisture, great lines often arise, i.e. very fast weather. In addition, the days are still relatively long.

Overall, the variability is definitely lowest in December, but all three months can have fantastic weather or sometimes poor conditions.

In what weather conditions will the 1500km be achieved?

This is a special situation, it might happen once or twice in the entire southern summer. Alexander Müller and Guy Bechthold always make great flights in these conditions. The situation is such that humid air has flowed into all of Namibia. But only very moderately humid. Homogeneous cumulus clouds then develop from the mountains in the west to Botswana in the east. In the afternoon there are no thunderstorms, there is a relatively weak easterly wind or even calm as the air has flowed in from the northeast and nothing follows. Bostjan then also achieves huge triangles.

In these conditions, thermal activity starts very early, sometimes at half-past nine, because there is only the nocturnal inversion through radiation and not through the cold air flowing in from the west. If you sit at the table in the evening and it blows like crazy from the west, then you know: The next day the relatively cool air is there and it is no good initially.

Bernd Goretzki

Bernd Goretzki