Interview of Clément Corbillé and Ludovic Mondésert who did a “Tour de France” in glider.

In our series, the TopMeteo pilots, we interviewed Clément Corbillé and Ludovic Mondésert, two French glider pilots about itinerant gliding. Indeed, last year, the two friends used an LS6 to do a “Tour de France”: one was piloting and the other was in charge of the car and trailer. Delighted by their experience they would like to see bigger this year and TopMeteo is happy to accompany them again.

Hello, thank you for this interview. Could you start by introducing yourself?

Clément: My name is Clément Corbillé and I’m 22 years old. I am a student in an engineering school in Tarbes named ENIT in my 4th year. And otherwise, on the aeronautical side, I started gliding very early, around 2010, because my dad is a glider pilot and is in charge of the club of Graulhet in the Tarn area (south west France) called ATVV (Association Tarnaise de Vol à Voile). Since then I have flown a lot, mainly in glider and I have been instructor for 3 seasons now. I have a little bit more than 1500 hours and I do a lot of cross-country, mainly doing long flights for the Netcoupe (the “French OLC” based essentially on cumulative distance flights). I am a competitor, too. I’ve done a lot of competitions, even if it’s not what I prefer. I better like this type of flights we made in this “Tour de France”, I mean long flights. We can also say that we are both involved in a very active Youth glider pilots Club which brings together young pilots from the south-west of France. It is called SWAF (South West Air Force, it is also a homonym of “Soif” in French meaning Thirst).

Ludo: Ok, so, I’m 23 years old. I started flying in Toulouse, at the Bourg St Bernard Club called AVAT (Association Vélivole et Aéronautique Toulousaine) in 2012, by luck. I always wanted to be an airline pilot, but I didn’t start for that. In addition, I discovered other jobs, so I changed my mind and decided to become air traffic controller. I’m going to graduate soon and for the past year I’ve been working in the aera control center at the CRNA Est (Centre en Route de Navigation Aérienne Est) based in Reims (which manages the airspace in the north east of France) and I’ve been flying at the Club of Châlons-en-Champagne (which should have normally hosted the World Gliding Championship in August 2020). I go cross-country as soon as I can. I’ve done a little bit of competitions like Clément: Two French junior nationals and some regional competitions. I didn’t go there with the goal of winning, but more because it was interesting. It was also a good opportunity to fly elsewhere with other pilots and to improve my flying skills. But since I discovered the itinerant gliding last summer by flying around France with Clément, I know that it is that form of gliding that I prefer. No question.

Can you tell us more about your first “Tour de France”?

Clément : We have been thinking about it for several years. But between everyone’s availability and the experience we wanted to acquire before starting it, it only came up last summer. The objective was both to experiment new things and to discover a new type of flight. We also wanted to make people talk about gliding and itinerant gliding. To show that you can make beautiful flights and that gliding is not limited to tasks where you come back every day to your home field.

Ludo: So we set off: We did 8 stages, 4 flights each. Graulhet to Sainte Foy la Grande in the South-West, then we went up to La Roche sur Yon (west France) then we joined Albert (north Paris), Chalons en Champagne (east Paris), Challes-Les-Eaux (north west part of French Alps), St-Crépin (central French Alps), then we wanted to reach Brioude in the Massif Central but the crossing of the Rhone valley ended with an outlanding near Montelimar. So we joined Brioude by car. Finally, we went back to Graulhet to finish the loop. In total we flew 3003km.

Clément: We also met a lot of people. Every time we stopped we had a very warm welcome. On top of that, we talked to many people from different clubs, by message, on the phone. They gave us advises and information about the availability of their clubs. So yes, we met a great welcome.

At what points were your journeys organized in advance?

Clément: It was planned in a way that we had the logistics ready. We had the glider, the car, the trailer. For the rest, we had some idea of where we wanted to go, which club we would like to visit. We were thinking the night before the flight: “okay, we’ve got this weather. We think we can go that far. On this road, we’ve got these clubs, and if it’s really good we can get further up to that airfield”. And so, every time like this. Then we contacted the clubs where we could potentially land as we needed to make sure that we would be able to take off again from this selection of airfields. Then, on the day, depending on the pilot feeling, we kept in touch, and adapted the strategy. Sometimes it was a much longer flight than we could imagine. So, it wasn’t fully predictable but there was a plan. We were never 100% sure where we’d land. But it worked quite well.

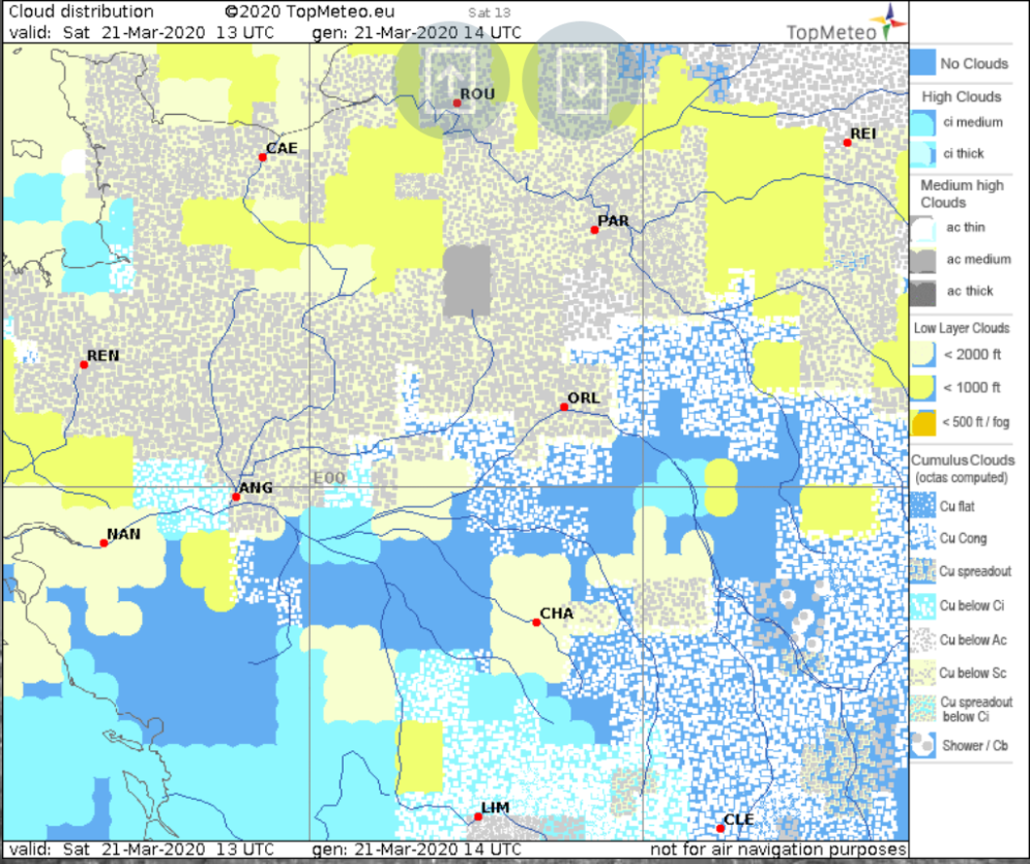

Ludo: The weather analysis part was important to us. Topmeteo had already sponsored us and so we were looking at the weather forecast and its evolution for the two or three days before to plan the best possible in advance. This helped to have a “big plan” and then the day before, we checked again and obviously, again just before take-off. We were pleasantly surprised by the result. It fit in well with what happened. I remember the Albert to Châlons flight, via Boulogne sur Mer. We’d seen that there would be a spread out on the return leg from Boulogne sur Mer leg. And it was exactly as planned: I struggled for a while, but fortunately, as planned, the weather improved after Albert.

Clément: We had really good use of the service. In Club, we rarely look at the forecasts more than 200km away from our course, whereas we used a lot of the Central European and French maps to anticipate the weather. Even though we had a great week, we were always ahead of poor condition. So we really needed to anticipate. For example, for the flight to Albert: we knew that Normandy wasn’t expected to have a good weather for the following days so we needed to go further and join Albert (north of France). And indeed, we would certainly have lost a lot of time if we hadn’t done that.

What surprised you most doing itinerant gliding?

Ludo: The really interesting part was flying to a lot of places in France very quickly. Because of this, we met a lot of different aerologies in a few days. We went from plains to mountains. And even between two different plains it was not the same conditions: it makes you wonder about the margin of progress that you have, due to local specificities. I remember the flight between Challes and St-Crépin (in the Alpes), I had already flown quite a bit in the Pyrenees, a bit in St-Auban but I still don’t think I have a lot of mountain flying experience. It was interesting to see how much more comfortable I am in the plains (smile).

Clément: The other thing is that we didn’t have to come back to the departure point, so it opened up a lot of possibilities. If we had to go home in the evening, we wouldn’t venture as far in weather that seemed more or less insubstantial to us. During the “Tour de France”, we had the constraint of moving forward, and we knew that if we ever ended up in a field, the car would come to retrieve us, no matter what. Well, it allowed us to explore the weather that at first glance did not seem very welcoming, and finally we realized it was working. So, in terms of thermal experience, it was great. For example, the flight from La Roche sur Yon to Albert, when at the end, the sky was totally grey, we contacted Albert to tell them that I was about to arrive, they didn’t believe it. It was raining on the ground!

Ludo: When I told them we wanted to come to their airfield, they laughed! They said, “You’ll never make it, it’s not possible.”

Clément: So that opens up new perspectives. It allows us to make flights that we would never do if we had to go home.

Did you try TopMetSat?

Ludo: Yes, on the flight to Albert, we were looking at the satellite images. With the loop mode. We could see the rain front being evacuated as Clement moved forward. It was good to have that confirmation.

What is your favourite Topmeteo product?

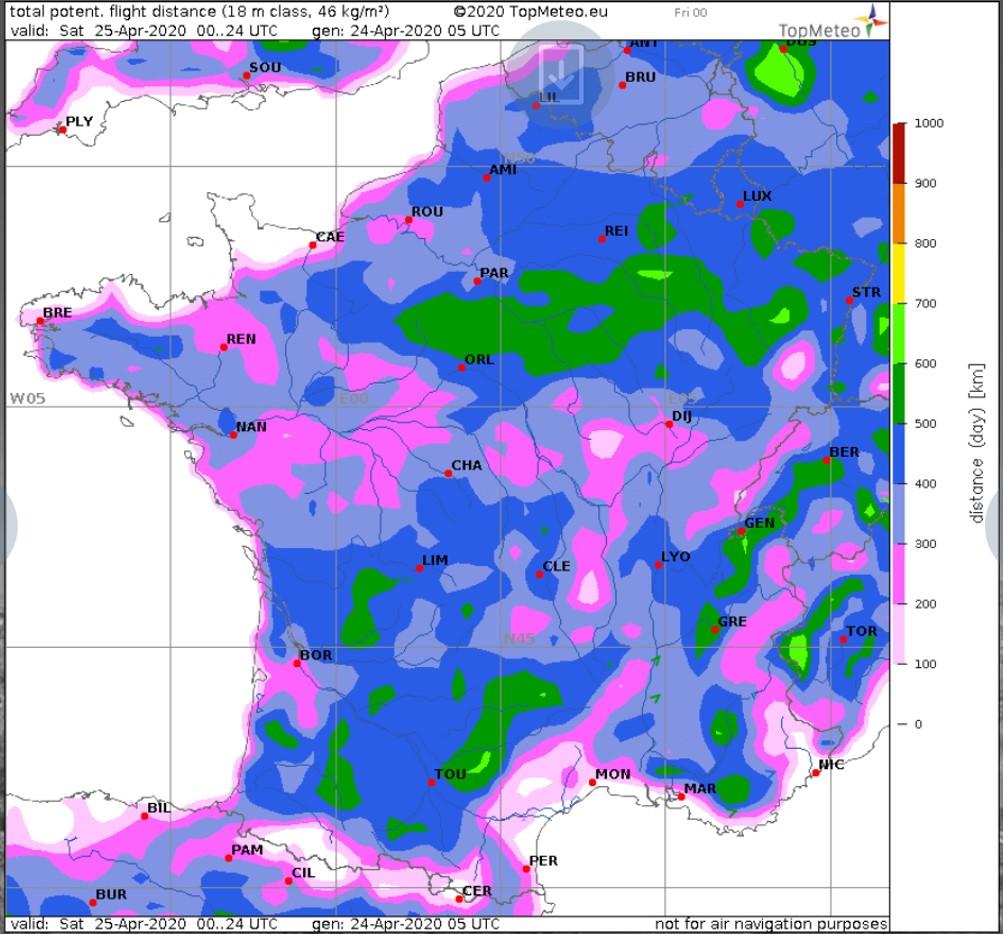

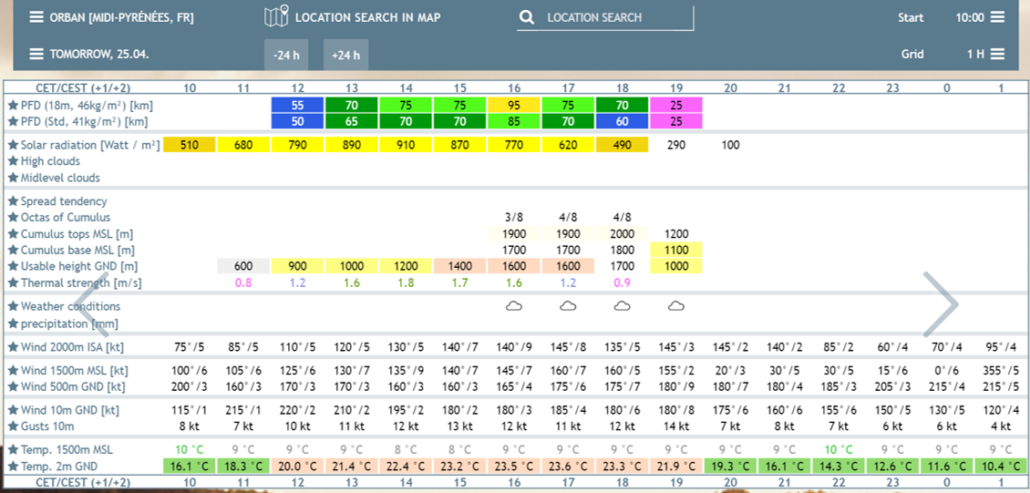

Clément: From my point of view, I like to start straight with the PFD (Potential Flight Distance) map, just to have an idea if it’s going to be good or not… This gives a first and easy overview. Afterwards, I naturally check the details of the different maps. My tips: I only use the 18 meters map even if I am flying club class, because what interests me is knowing which sectors will be better, and I find that it has more contrast on the 18 meters map.

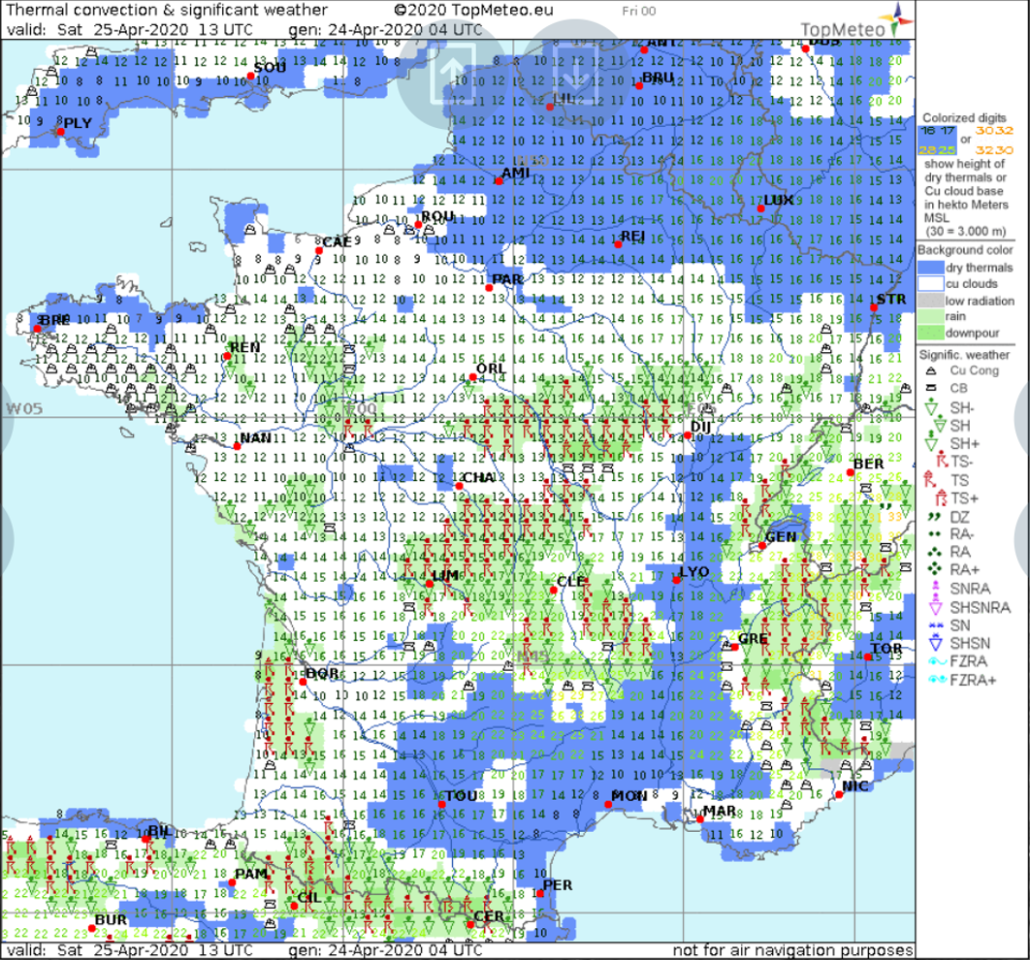

Ludo: Same, I use the PFD first and then I display the Thermals map and the one with the cloud cover to check from “where” does the PFD “come from”. And then when I have an idea of where I want to go, I look precisely at the airfields on the route to see the expected conditions at the time I think I will fly there.

Potential Flight Distance

Thermal map

Site Forecast

And if you had to name the next development, what would it be?

Clément: Ah, I have a thing. It would be nice to have the wave forecast. I don’t do a lot of wave flying but from time to time when I go to the Pyrenees, it would be nice.

We know other pilots are asking for it and we work on it. As usual it takes time to finalise a product we are really happy and proud about. So, we cannot say when it will be available, but we are working on it.

So now, what’s the plan for this year… if the restrictions linked to COVID-19 are removed by July?

Ludo: Last summer we stayed in France. We had an idea of the different clubs we wanted to visit. We did it in 8 days, whereas we had planned to do it in two weeks. Well, we had great weather, but all in all it went so well… This summer we’re are planning to give ourselves another two weeks, but then why not trying to go a bit further if the weather is good and we are allowed to do it? For example, we have never been in Spain. We heard about it : Pilots tell us about the great conditions there so why not crossing the Pyrenees and go to Spain to see some high cloud bases ? That’s a first idea. And then, depending on the weather and the COVID, why not taking a little trip to Germany? So yes, why not a “Tour de France” but from the outside?…

Clément: So, for today, we have no clear plan about where to stop yet, but the desire to go a little bit further is clear, still promoting the itinerant gliding. And obviously, trying to have a maximum of great experiences and adventures to share during and to tell afterwards.

Ludo: So yes, nothing planed but the desire to go further. And if all goes well, we will have a very nice glider to help us but nothing is signed yet.

What do you mean by that?

Clément: We talked with Schempp-Hirth and we could use their Discus2c- Fes. It would be super cool.

Ludo: That could be nice because it reduces the likelihood of outland. We can plan longer flights and then on certain stages, we can leave the trailer. It would be good to get rid of that weight for two or three days.

Clément: Yes, the FES will allow us to make more audacious flights. It will open up a new field of possibilities for us: not flying where we cannot land as it is still a glider but just being able to “skip” areas where the airmass is “dead”. It would be great if it’s confirmed.

Ludo: But the goal will still be not to turn the engine on!

Do you want to add something?

Clément: If some people are thinking of trying out itinerant gliding… There are a lot of constraints at first glance, but you have to give yourself the resources because it’s different from gliding in a club or in a competition, and it’s really amazing!

We keep our fingers crossed that you can do your “oversized Tour de France” this year, and we are proud to support you. Thanks again for the interview and for sharing your gliding adventures to the pilots but also to the public audience.

You can follow their aventure on Facebook and Instagram!